Research

Aim and Approach

My research in systems neuroscience aims to understand how neurons cooperate in a massively interconnected network to generate high-level cognitive functions. Keeping the mind-body problem in mind, I believe that an answer to this question entails creating a mechanistic understanding of how from unreliable spiking neurons, connected with plastic synapses, emerge stable structures that support reliable functionality.

To dissect these basic mechanisms, my main approach is to use rich behavior repertoires to gain access to and create simpler representations of key elements in activity of neuronal ensembles. Purposely-using complex behavior may seem paradoxical but, put simply, in taking an elaborate data set or problem and projecting it onto many dimensions it is often much simpler to untangle separate components and identify relevant patterns. In fact, this principle underlies the success of deep artificial neural network algorithms and leading hypotheses about the function of the neocortex.

Another tenet I hold dear is the role of time as a key variable ("well duh" says the ethologist). Often, neural systems are treated as (pseudo) static - frozen computing machines. Such approach, in effect, flattens the dynamic nature of the brain and makes many processes, different learning algorithms for example, become indiscriminable. In all my experiments, the time and sequence components of behavior serve as strong constraints on potential theories that could explain my results.

Canaries - Excellent singers and fantastic models for investigating neural mechanisms

Canaries, like starlings, nightingales, and blackbirds (to name a few), are virtuosos capable of producing minute-long songs composed of many different individual notes. These notes, often called syllables, are sung in variable sequences that almost never repeat exactly and create an impressive repertoire. Such behavioral richness allows investigating the mechanisms responsible for producing complex behaviors but also creates challenges in annotating the different syllables and in statistical analyses.

Working memory in canary song syntax

The brain executes precise motor elements, gestures or vocal syllables, in variable sequences. This cognitive ability allows creativity and evolutionary fitness and, when damaged by disease or aging, leads to marked motor sequence generation and comprehension dysfunction. A key property of motor sequences like language, dance, and tool-use are long-range syntax rules - element-to-element transitions depending on the context of multiple preceding elements across seconds, or even minutes, of behavior. To create such syntax rules the memory of the long-range context needs to impact the premotor neural activity.

Canaries are an excellent model for investigating the neural mechanisms supporting long-range syntax rules. Canary songs are comprised of repeated syllables, called phrases, that typically last one second. The ordering of phrases, like human language, follows long-range syntax rules [1], spanning several seconds. My latest work exposed encoding of long-range context in the premotor circuits of freely singing canaries. This encoding occured preferentially in phrase transitions depending on long-range song context. This form of working memory could support the complex syntax rules in canary song - demonstrating, for the first time, a connection between neural activity and behavior in songbirds that shares time and sequence properties resembling human behavior.

Primates - Excellent learners of abstract concepts

Primates often need to choose a course of action in complicated situations. For example, one may be forced to choose a wine goblet from which to drink and base this choice on multiple cues like the source of Iocane powder and the fact that your oponent bested both your giant and your spaniard. This commonplace scenario is an example of complex concept-based or rule-based behaviors - situations where an action or a label is assigned to a multi-cue pattern based on individual cues and their combinations. If both the labels and the cues are binary then deterministic concepts can be described by truth tables or by boolean expressions.

Models of human visual-feature-based classification learning

The task of labeling, or classifying, multicue patterns, as shown in the above example, is very common. The rules used for classifying a set of visual stimuli may change (e.g. in other occasions the cheese and the bread are more important cues for choosing which wine to drink) and we can quickly and advantageously adopt new complex rule-based behaviors. But, with N binary cues in each pattern the number of possible patterns is 2^N and the number of possible rules for classifying those patterns into 2 categories is 2^(2^N). Holding all those possible rules in memory is - inconceivable! - and still, we regularly and effortlessly learn new rules, often using an impoverished sampling of the stimulus space. The question of how we do it and what simplfying assumption we make is interesting both psychophysically and clinically.

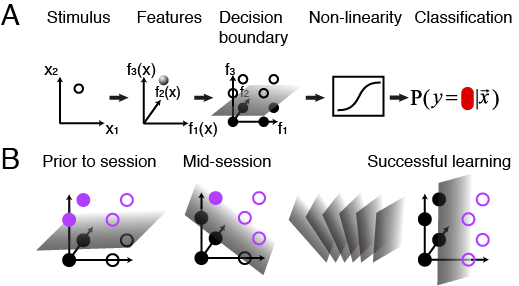

(A) Graphic representation of the mixture of features-based model. The classifier is a hyperplane in the space of features, f, of the pattern x. The decision boundary is a plane in the features space. (B) Graphic representation of learning dynamics. At the start of the experimental session, subjects’ decisions can be explained in terms of a hyperplane in the high dimensional space of pattern features. During the learning process, this hyperplane is shifted and rotated in the features space, getting it closer to the correct rule.

My work in human psychophysics replicated the observation [2] that population average performance depends on the classification rule and revealed that individuals learning the same rule can have very different learning curves despite seeing the same step-by-step order of patterns. To capture this individuality, I modeled the subjects' belief about the rule as a probabilistic classifier based on visual features of the patterns (A). To describe the learning dynamics I used a simple reinforcement-learning step that shifts that belief (B). This framework captured individual learning behavior surprisingly-well and reflected the important role of subjects’ priors. To "cross validate" the fit to individual subjects I showed that these models predict future individual answers to a high degree of accuracy and can be used to build personally-optimized teaching sessions and boost learning.

Neural correlates of classification learning in monkeys

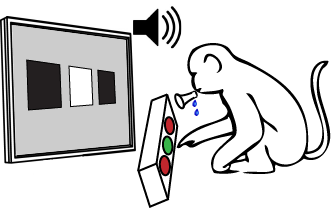

Classification tasks are used to explore learning strategies in healthy human subjects and in patients. The neurophysiological underpinnings of multicue pattern classification are commonly studied in monkeys - animal models capable of performing complex visually-guided tasks. But, in many of these animal studies it is impossible to observe how neurons form representations as learning progresses and gradually become relevant to the final classification being imposed. This is mainly because most experiments follow extensive training and the neural correlates relate more to the final representation, perception, and recognition, and less to the gradual learning process. The extensive training also prevents investigating many rules in the same animal - limiting general conclusions.

My work took an opposite approach. I trained my monkeys, Gato and Dimi, to perform classification learning tasks on 3-bit binary patterns (my human subjects used 4-bit and 5-bit patterns). Then, I recorded activity of single neurons while the animals learned eight conceptually-different rules they never encountered before. To investigate neural dynamics I represented single neurons' changing stimulus selectivity as a trajectory in the space of visual features of the patterns - echoing the approach I took in modeling human beliefs. Since the rule being learned can be described as a direction in this space, my approach allowed comparing learning-related neural dynamics across sessions of different rules in geometric terms - projections of the neural trajectory onto the rule. This framework exposed different learning-related dynamics in various brain regions - suggesting different roles in learning - and also allowed predicting next-day performance from the neural activity.

Artifical neural networks - Excellent toy models

David Marr famously outlined a framework for analyzing neural mechanisms in three conceptually-different levels - A certain cognitive function at the top level is carried out by a mid-level algorithm that is physically-implemented by neural activity at the bottom-level. The field of Systems Neuroscience is substantially-shaped by Marr's framework. My experiments in primates and songbirds purposefully-use time scale separation between ongoing neural activity and its behavior correlates to tease apart the physical and algorithm levels. A complementary approach to dissecting neural mechanisms uses simulated neural networks as toy models - In-silico animal models allowing access to all of Marr's levels.

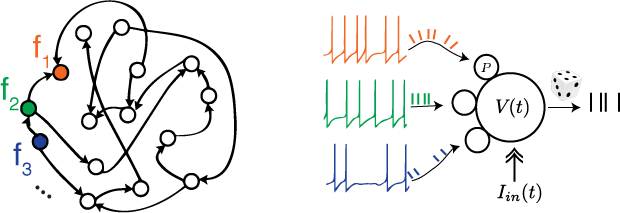

Developing an empirical characterization of motor learning in biological systems

Movement control ties brain activity to measurable external actions in real time, providing a useful tool for both neuroscientists interested in the emergence of stable behavior, and biomedical engineers interested in the design of neural prosthesis and brain-machine interfaces. My work approached the question of motor skill learning by introducing artificial errors through a novel perturbative scheme, amenable to analytic examination in the regime close to the desired behavior. Numerical simulations then demonstrate how to probe the learning dynamics in both rate-based and spiking neural networks - revealing both properties of the learning algorithm and internal dynamics of the toy models. These findings stress the usefulness of analyzing responses to deliberately induced errors and the importance of properly designing such perturbation experiments. This approach provides a novel generic tool for monitoring the acquisition of motor skills.

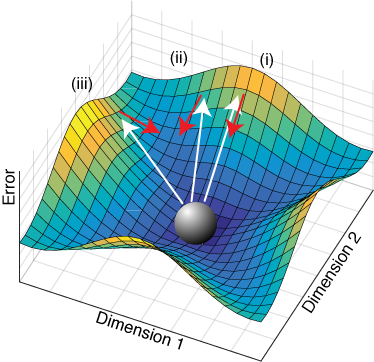

Conceptual illustration of perturbation in a nonlinear system. Perturbations are akin to kicking the ball, which represents the fixed point in steady-state at the origin of the error manifold, along the white arrows. The learning response, represented by the red arrows, depends on both the direction and magnitude of the perturbation and can be, like the linear case, simply contracting (i) or also rotating (ii,iii).

Tools

I enjoy developing hardware and software tools. Neuroscience research is, almost by its nature, interdisciplinary. Technical problems arising in research have, therefore, a unique interdisciplinary flavor. Creating solutions to these problems is fun and very rewarding because they immediately advance my work and contribute to the work of others.

TweetyNet - A machine learning tool for annotating complex song

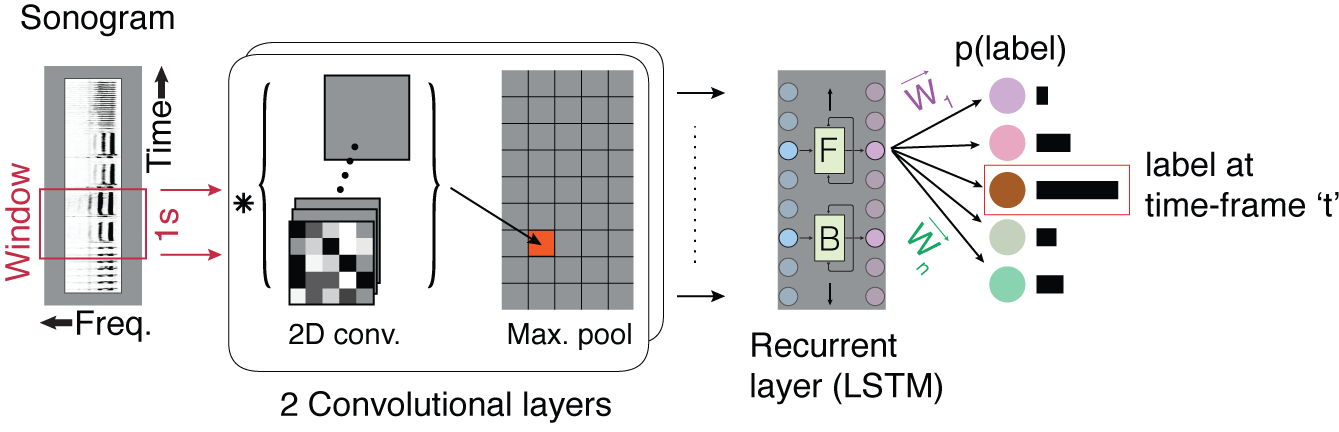

Manual song annotation is a highly time consuming task that impeded the advance of complex songbirds as models for neuroscience research. I developed a deep neural network architecture, TweetyNet, to automate this task. I used TweetyNet to process more than 5000 songs in my neural imaging work – a task that takes years if done manually. The access to thousands of songs yielded a tenfold precision increase in canary syntax analysis and allowed me to gather preliminary data for my current research aims. To test TweetyNet in other species, I initiated a collaboration with David Nicholson who studies Bengalese finches in Emory University. Compared to published state-of-the-art algorithms, TweetyNet performs twice as well using half the training data. TweetyNet is open-source and is being tested in vocalizations of additional songbirds, as well as mammals.

Next generation ultramicroelectrodes

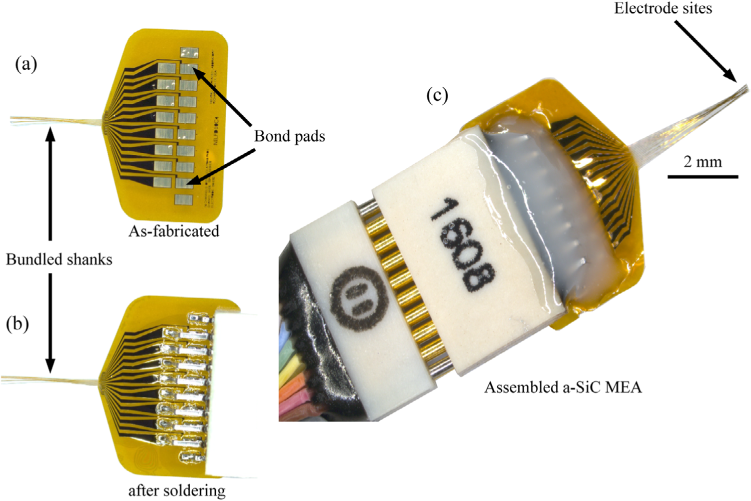

Foreign body response to indwelling cortical microelectrodes limits the reliability of neural stimulation and recording, particularly for extended chronic applications in behaving animals. The extent to which this response compromises the chronic stability of neural devices depends on many factors including the materials used in the electrode construction, the size, and geometry of the indwelling structure. In collaboration with Stuart Cogan’s lab at UT Dallas, we developed microelectrode arrays based on amorphous silicon carbide, providing chronic stability and employing semiconductor manufacturing processes to create arrays with small shank dimensions. My role in the project was to design electrode geometries, to test their electrochemical properties ex-vivo, and to test them by acute and chronic in-vivo recording in zebra finches.

Miniaturized fluorescence microscopes

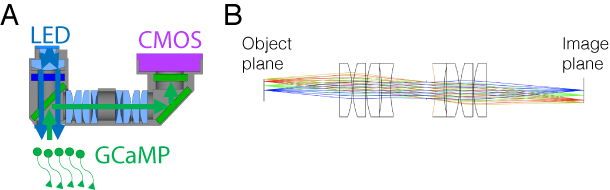

In the last several years there is an explosion of new techniques for fluorescence imaging in freely-behaving animals. Our lab pioneers several such tools (e.g. 1 and 2 color FinchScopes) used in small lab animals. Together with the Davison lab and the optics guru Anderson Chen we develop a new miniscope design - the wide field miniscope (A). This light-weight (<4.5g) miniaturised fluorescence microscope is small enough to be used in mice offering optical access to areas up to ~3 X 4 mm - a substantially-increased imaging areas over current systems while maintaining single-cell resolution. The system is based on a 3D-printed housing and off-the-shelf components that are economical and readily modifiable for different experimental demands. My role in this project was to model the optical system (B) and help designing resolution tests comparing the model expectations to the performance of the constructed prototypes.

References:

[1] Markowitz, J. E., Ivie, E., Kligler, L. & Gardner, T. J. (2013) Long-range Order in Canary Song. PLOS Comput Biol 9, e1003052.

[2] Shepard RN, Hovland CI, Jenkins HM (1961) Learning and memorization of classifications. Psychol Monogr 75(13):1–42.